Silent struggle in Chechana camp: 60% girls lack access to education

For over four decades, the Chechana Refugee Camp, in Kohat district has sheltered generations of Afghan refugees fleeing conflict in their homeland. Today, it faces a silent crisis: the systematic exclusion of young girls from education.

According to a UNHCR official with eight years of experience in the camp Anayat Ullah, 60% of girls here receive no formal education. The 40% of who attend school, all are forced to drop out after the 5th grade due to economic hardship, cultural constraints and a lack of accessibility to facilities.

The nearest government school is located 7km away, a distance that is both financially and culturally prohibitive for many families.

A father’s plea

A long term resident of the camp and father of three daughters, Ismail shared his struggle with Aaj News. He said “I have begged UNHCR officials and other organisations for years to build a school here.

They collected data and made promises, but nothing changed. My daughters deserve an education, but now can I send them 7km away when we can barely afford food?”

His plight reflects broader issue. A report from the Kohat District Education Office found that extreme poverty defines life in the camp, with most families surviving on less than Rs300 a day.

The report also stated that “education is not a priority for poorer families”, citing early marriage and domestic labor as reasons girls are kept out of classrooms.

A young teacher’s initiative

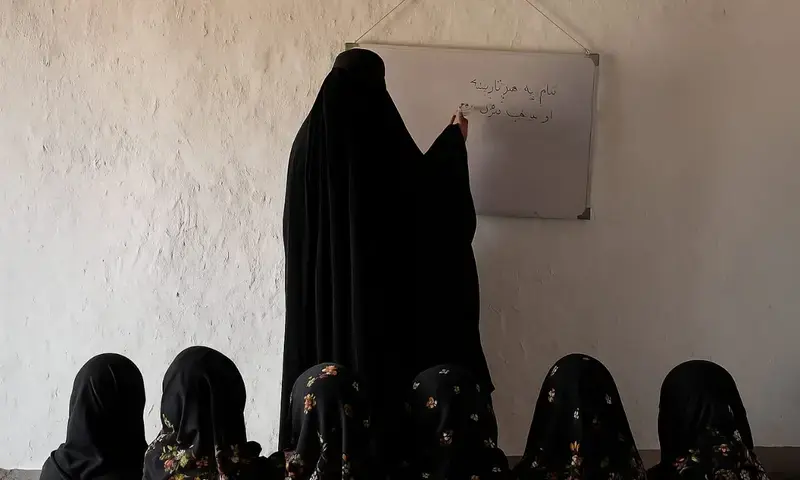

In the absence of formal educational support, 18-year-old Maria decided to take action. Four years ago, she began teaching girls in her home using religious texts like the Quran and Taleem-ul-Islam, the only materials available to her. Today, she educates over 50 girls in a small room donated by a neighbour.

“I teach them to read and write through these books,” Maria told AAJ News. “But we need proper supplies, not just religious texts. I dream of becoming a trained teacher, but for now, this is all I can do.”

While her efforts represent resilience, they are insufficient. The camp’s only official school serves just 136 students and remains inaccessible to children from two of the five villages due to distance.

Government acknowledgement

Deputy director of the Provincial Education Department, recognised the educational gaps faced by refuged communities. “The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government, in collaboration with federal authorities and UN partners, is aware of the constraints faced by Afghan refugees in camps like Chechana.

We are working on a phased plan to improve access to education, particularly for girls by establishing temporary learning centers and integrating refugee students into nearby government schools.”

Challenges ahead

Despite Maria’s classroom offering a glimmer of hope, it faces significant challenges. Lacking formal training, she relies solely on religious texts and her students do not receive structured curricula or recognised certifications.

Without external support, the sustainability of her initiative remains uncertain and there is a risk that girls will be left behind once they outgrow their lessons.

A path to change

While organising the camps like UNHCR have historically provided aid, their efforts have not kept pace with the camp’s growing needs. However, solutions may lie within the community itself.

Maria’s classroom serves as a working model trusted, culturally appropriate and scalable. With targeted support for teacher training materials and infrastructure it could evolve into transformative educational center.

Similar successful initiative have occurred elsewhere. In Punjab’s Kot Chanda Camp, the late Afghan refugee teacher Aqeela Asifi started with a borrowed tent and eventually established nine schools, one of which was formally recognised by the Punjab Education Department.

In Iran, Afghan refugee women have been trained through UNESCO-UNICEF programs to become certified teachers and the Norwegian Refugee Council has helped construct safe energy-efficient schools.

Maria’s classroom could follow this successful path, transforming from a small initiative into a structured, recognised educational center if authorities and aid agencies choose to invest in her potential.

As Ismail poignantly asked, “How long must our daughters wait?” The answer hinges on whether policy makers and partners choose to act now and replicate these proven solutions.

For the latest news, follow us on Twitter @Aaj_Urdu. We are also on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube.

Comments are closed on this story.